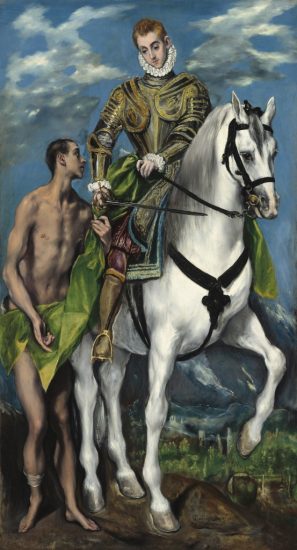

Saint Martin and the Beggar, El Greco, 1597–1599, National Gallery of Art (Washington, DC).

FIRST READING:

Sirach 35:12–14, 16–18

October 27, 2019

John Henry Newman was canonized a saint of the Church two weeks ago. He was a leading member of the Oxford movement. This was a group of 19th century English Protestant clerics and academics associated with the University of Oxford who delved deeply into the history of the Early Church. They discovered that the church was based on the witness of the apostles and that it expressed itself in Sacraments, most especially the Eucharist, and in service to the poor. The movement’s adherents who thought that this apostolic origin meant obedience to the Pope left the Anglican (Episcopal) church and became Roman Catholics, but all those who were loyal to the movement celebrated the Eucharist with a belief in the real presence and served the poor. St. John Henry Newman joined the Oratorians after his reception into the Catholic Church and moved to the industrial city of Birmingham where he lived with working class people.

This was one of the great precursors of the Second Vatican Council which called for a “resourcement:” a return to the sources of the Scriptures and the early Christian Writers, usually called the Fathers. The council itself called the Eucharist “the source and summit of the Christian Life” and the Jesuit Order was inspired to make “the preferential option for the poor” the lens through which all things were viewed.

Sirach, from whom we read today, would have understood.

Both the members of the Oxford Movement and the Fathers of the Council understood that the world was changing and that, even if many of those changes were good and wholesome, some were far from it and we would need to change our relationship with the contemporary society. They had the insight that they needed to root themselves in their tradition to truly understand who they were.

Ben Sirach knew the same thing in Jerusalem circa 200 BC. As we have seen, he was a teacher of the young Jewish elite. These young men would have lived among the Greek rulers and experienced Greek, or Hellenist, culture every day. Much of it was attractive to them, but the real danger was that it was everywhere and in everything.

There was a temptation to try to graft Jewish limbs onto a Greek tree. Many did so: what we now call wisdom literature prided itself on being international. The great and good of Athens and Alexandria would have accepted the same precepts and would expect their counterparts in Jerusalem to do the same. Ben Sirach was not a provincial, he knew the other systems of thought and sought whenever possible to make connections. Yet unlike many of his contemporaries he engaged in a “resourcement.” He began with his sources. His book begins:

All wisdom comes from the LORD

and with him it remains forever.

To whom has wisdom’s root been revealed?

Who knows her subtleties?

There is but one, wise and truly awe-inspiring,

seated upon his throne:

It is the LORD; he created her,

has seen her and taken note of her.

(Sirach 1:1–9)

That would have gotten his students attention. Wisdom is not the creation of even the wisest sage, but God himself. His concern about the poor would also have been striking.

Like one who kills a son before his father’s eyes

is the person who offers a sacrifice from the property of the poor.

The bread of the needy is the life of the poor;

whoever deprives them of it is a murderer.

To take away a neighbor’s living is to commit murder;

to deprive an employee of wages is to shed blood

(Sir. 34:24–27)

These were rich children, and this was a real issue for them. Note that this concern for the poor is connected to worship and indeed makes it acceptable to God.

To keep the law is a great oblation,

and he who observes the commandments sacrifices a peace offering.

In works of charity one offers fine flour,

and when he gives alms he presents his sacrifice of praise.

(Sir. 35:1–2)

“Oblation,” “peace offering,” and offering of “fine flour” are all terms of sacrifice and worship. He is saying clearly that charity is itself a form of worship and certainly must be present before any cultic act would be deemed acceptable.

Ben Sirach’s students needed to be reminded that they may become important officials, but they can never bribe God with sacrifices or honors. He is completely just and cannot be swayed by human flattery. Sacrifices will not put him in our debt. As we have seen time and time again in the Old Testament:

Yet he hears the cry of the oppressed.

He is not deaf to the wail of the orphan,

nor to the widow when she pours out her complaint;

(Sir. 35:13–14)

And:

He who serves God willingly is heard;

his petition reaches the heavens.

The prayer of the lowly pierces the clouds;

it does not rest till it reaches its goal,

(Sir. 35:16–17)

The section concludes with:

God indeed will not delay,

and like a warrior, will not be still

Till he breaks the backs of the merciless

and wreaks vengeance upon the proud

(Sir. 35:19–20)

Whether in 19th century Oxford, the Jerusalem of 200 BC, or the Rome of the 1960s, the pattern is still the same. If we delve into our tradition, we will discover that the worship of God and concern for the poor are inextricable. They cannot be separated, and they strengthen each other. It needs to be the same with us in Brooklyn in 2019. We are expending considerable sums to rebuild our church. It is not only to prevent it from falling down after 150 years but more importantly to improve our worship. We will know if our worship on Sunday has been effective by how well we serve the poor the rest of the week and, alas, there seem to be more and more opportunities to do so every day.